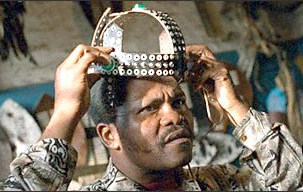

With the help of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, founder Joseph

Shabalala

played an integral part in helping end apartheid in South Africa.

The steady hand and creative vision of Joseph Shabalala have been

the guiding force behind Ladysmith Black Mambazo since the group was formed

in 1964. In the soaring bass, alto and tenor harmonies of Ladysmith Black Mambazo,

Isicathamiya, a tradition of Zulu choral music that arose from the squalid conditions

of existence in South African gold mines found new expression, and apartheid

a formidable foe. During the struggle against apartheid, Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s

signature harmony lent a voice and a face to the hardships of South Africa’s

black majority, and was an important aspect of the cultural front, which eventually

defeated apartheid. The world took notice of Ladysmith, and the band went on

to win a Grammy Award for best folk recording in 1987, and they have been nominated

six times since. The band’s collaboration with acclaimed director Eric

Simonson on The Song of Jacob Zulu, and another with writer Ntozake Shange on

Nomathemba, which premiered in 1993, were both hits on Broadway and established

the group as one of the pre-eminent interpreters of Zulu choral music.

Shabalala’s success, however, came at no small price. He was widely criticized

for violating the ban on trade with South Africa when Ladysmith recorded with

Paul Simon on the Grace Land album. And in 1990, Shabalala’s brother Headman

became a casualty of apartheid-related violence.

The dividends of liberation remain elusive to many in the new South Africa,

and Joseph Shabalala and Ladysmith Black Mambazo have now focused their great

talents and reputation on alleviating the social ills that plague the country.

The group’s Black Mambazo Foundation seeks to empower and promote self-reliance

among women, the urban poor and victims of HIV/AIDS by providing sewing classes

and free sewing machines to participants. This, coupled with the stress of a

hectic schedule of international appearances and an assistant professorship

at the University of Natal, has kept Shabalala more than busy. It’s also

prevented him from his longtime dream of establishing a Mambazo Academy to teach

and preserve South Africa’s indigenous cultures.

Africana recently spoke to Joseph Shabalala about his experiences over the years

– musical and political.

LBM has collaborated with artists ranging from George Clinton to Dolly Parton

and Stevie Wonder. How important are these collaborations to your own creative

process, and to the group’s creative energies?

First of all, to work with other people gives us more exposure to the young

and old. But it does not mean that we must run away from our a capella, because

we do this with the purpose of developing the culture and developing the people,

because people started to forget themselves. But God will be disappointed if

he gives us something and then we run away from it. But it is good to shake

hands with black and white, with their guitars, with their drums. It is also

good for us to stay with our harmony because they love us because of this harmony.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo are often described as cultural emissaries of South

Africa. How important is it for the local cultures of South Africa to be maintained?

This is very important because it takes the children back and it makes the children

demand that this music be taught at school, because all along everyone has looked

down on this music. But because of Black Mambazo, now the children are demanding

that this music be taught in school. Which means that we are the witnesses of

the old people who now say that their dreams have come true.

A lifelong dream of yours has been to create a Mambazo academy of African music

and culture. How far along are you in the realization of this project, and have

you received any international assistance?

So far, there is no help. But I can say this, help is the [LBM] supporter and

they support us internationally and locally. My dream from the beginning was

an academy where I am going to teach the teachers who can understand how to

teach the people how to remember the traditional things, and how to combine

that with the knowledge from the school, not divide it as before. Financially

it is hard, not hard because they don’t have any money. I remember Coca

Cola was going to help, but they kept telling me to come back again, to hold

on maybe for two years and come back again. Politics, you see. It was all politics.

The dividends of the end of Apartheid have not been felt by many of the people

of South Africa, especially the youth. Will this pose a problem in the long

run?

The problem is there already. That’s why HIV has increased in recent years,

because of starving, because of homelessness. People must learn to help themselves

also. Freedom is there, and people can do whatever, but now we are trying to

help these women’s organizations that call themselves Kuyasa, which in

Zulu means “Here comes the light.” They work with AIDS infected people,

they sew clothes for them, and show them how to use sewing machines and how

to sell those products.

There is a young man in DC, Stanley Brady, who has been helping us with this

initiative. This year alone he sent twenty-two containers. We ran out of space

to store these things, and then we talked to social workers and they gave us

a big warehouse. We sorted out all those things and gave them away to the homeless.

How can people in our audience offer assistance to your foundation?

People can also visit our website www.mambazo.com to find out how to offer assistance.

How important was music in general and choral music in particular in the

struggle against apartheid?

The music was the key. It was like something that bridged the gap between [black

and white South Africans]. The music played a big role to bring these two nations

together because music knows no boundaries. White people supported us secretly

in those days, but they were not allowed to say anything. Our people, they get

strength through the music.

In 1987, LBM won a Grammy for best folk recording, and since then you’ve

also been in the movies like Song of Zulu and Nomathemba, and you were nominated

for six Tony awards. Is there in, your view, a common thread that links all

these?

Brother, these things make me have more energy to carry on but I can tell you

the truth, when it happened, somebody said look back and see what you have done.

But the dream still continues. It’s good to see a Grammy, but all of a

sudden I can ask you. But what is this for? I remember when we won the Grammy

award, we were on tour and the Grammy was sent home. When we arrived, people

were curious to know what it was, and we said that we did not know, but we just

won something called the Grammy awards. I remember many people; scholars came

to the airport to welcome us. It was the first time that a South African had

won a Grammy award. 1987 was something big, that’s why we had the power

to create the South African Traditional Music Association. Once you’ve

won something, you have power. Once you have passed the test, you have power.

Are you disappointed that since you won the award, few African artists have

won it since?

Disappointed? Never! When I did not win, I said it is for another person and

I cheered for that person.

Any message for your fans worldwide?

I’ll say this, which I know that they know! Peace, love and harmony. And

don’t forget that you make the music from the blood to the blood.

First published: June 18, 2003

The Africana

By Muna Kangsen